Download the full source code for the model here:

natehanby.files.wordpress.com/2019/02/computer-model-of-population-genetics.zip

The model is written entirely in Transact-SQL and is designed to run inside of Microsoft SQL Server Express, a free database engine which can be downloaded and installed from Microsoft here:

www.microsoft.com/en-us/download/details.aspx?id=29062

Change Log:

2019/2/5: Original Version of the Model uploaded.

This model tracks the genetic load of a population–across up to 32767 different possible genes, up to 255 variants of each deleterious mutation can be tracked. A genome with configurable properties is generated with random elements and remains consistent through each year of each simulation. A population of several tens of thousands of people can be simulated over many thousands of years, given a few hours to run on a typical desktop computer. Each person passes on genes to their offspring, plus new mutations, according to the principles of Mendelian genetics. By changing the settings of the model, different legal and cultural scenarios can be simulated to determine their effects on the future of human genetics.

The Implications of this Genetics Model on Human Suffering

The model keeps a metric of “child mortality” which records the percentage of people who die before age eighteen. This metric is used as a proxy for human suffering. The parameters of the model can be changed and experimented with to try to determine which social situations lead to a long-term permanent reduction in child mortality and which lead to only a temporary reduction.

Historically, high child mortality was how the population was kept in check. In the modern day, other methods of limiting the population are used, if any are used at all. Using the model, we can try to see what effects different methods of limiting the population have on genetic health, and, ultimately, the child mortality rate.

First, let’s start with settings that model pre-modern life, when child mortality was high: [Population Model with Natural State Settings.sql] (found in source code)

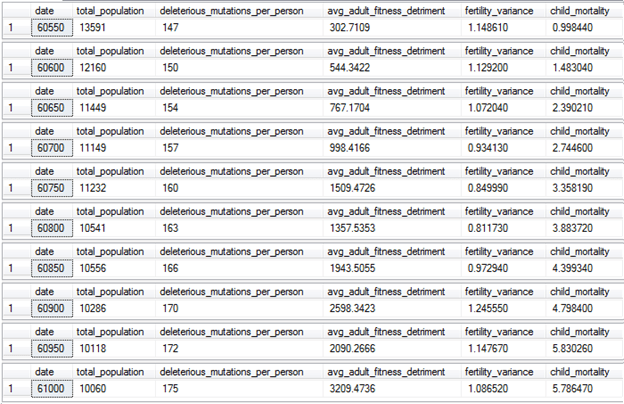

To generate the data used by this model, I ran the model with these same settings for two days real time, simulating a population of 13,000 or so over the course of 60,000 years. This was enough time to allow the mutations of most of the 20,000 possible genes that are modeled to reach an equilibrium state. The total number of deleterious mutations per person first broke 140 per person about 35,000 years into the simulation, and since then it has fluctuated up and down and has only slightly increased from that level. Here’s what the next 500 years looks like under the same natural state settings:

An explanation of how to read these results: The model is configured to report data on the population every 50 simulated years. It reports the year since the simulation started, the total population for that year, and the total number of deleterious mutations per person. It reports the average adult fitness detriment, which is modeled as a percentage increase in the rate of adult failure compared an idealized person with no genetic load. The fertility variance is how much each person’s fertility differs, on average, from the average fertility. This is an important metric for determining how much natural selection exists in the system. And it reports the child mortality rate, the percentage of people who die before age eighteen.

For these settings, families will simply continue having children every two years until they can’t anymore. The death rate is high and according to the settings, it increases as the population increases—this is how the population remains stable. Running the simulation, we find that under these settings, the child mortality rate has reached an equilibrium of about 47.5%—comparable to the historical level in many pre-modern populations.

A high child mortality rate in this scenario is inevitable due to the settings given. The death rate must be in equilibrium with the birth rate, or else the death rate increases.

Modeling Modern Western Civilization

So, with our goal of reducing human suffering from the natural state, let us try to alter the settings in such a way that the child mortality rate goes down and stays down.

First, we will take a naïve approach: We will reduce the death rate drastically—to represent the development of modern medicine. To do this, we will reduce the @child_mort_factor setting from 5000 to 200, representing a decrease in the number of people who die. We’ll reduce the @adult_mort_factor by the same amount. Additionally, the child mortality will no longer increase as the population increases—under the previous settings, the @child_mort_factor increased by 2000 points for every 2200 people who were present in the population. Now it will stay at a constant 200, never increasing.

To limit the population, we reduce the family size from as high as possible to two to three children per family. To still limit the population, we will cause an increase in adult failure when the population is over 13,000. This represents economic limitations to the population size and should keep the population from going much higher than what it was before.

We will also be forced to increase the @percentage_matching parameter, which is used to determine the efficiency of sexual selection. But since family size is lower, a higher percentage of people must successfully be able to find a mate, or the population can’t breed at replacement rate.

The new settings can be run from this script: [Population Model with Modern Western Life Settings.sql] (found in source code)

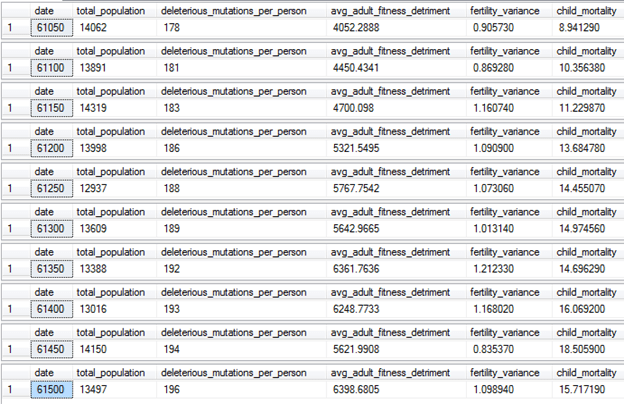

And here are the results:

Our naïve plan to reduce human suffering didn’t work in the long term. After the invention of modern medicine, the child mortality rate dropped to about 1%, but then after 500 years of mutations, the child mortality rate crept up to almost 6%. Furthermore, the genetic load has increased from 145 deleterious mutations per person to 175, and the average adult fitness detriment has increased by a factor of fifteen, representing many new highly deleterious mutations that freely persist in the population due to lack of natural selection.

Additionally, our population is starting to go into a very slow decline, as family sizes of 2 to 3 are no longer enough to sustain the population against these new higher levels of genetic load.

We need at least enough natural selection to remove bad genes as fast as they mutate. But it seems that modern life with low family size and low death rate does not provide enough natural selection.

Modeling Two-Child Family Laws

To make the problem even worse, lets run the model further, this time with settings that are based around the family size restrictions of the two-child-family policy of China: [Population Model with Two Child Family Law Settings.sql] (found in source code)

Under these settings, people have as many children as possible when the population is below 13000, but once it goes above 13000, a family size law of two children per family is implemented until the population crashes back to below 13000. Additionally, adult failure no longer increases as the population increases. Otherwise, the settings are the same as the Modern Western Life model.

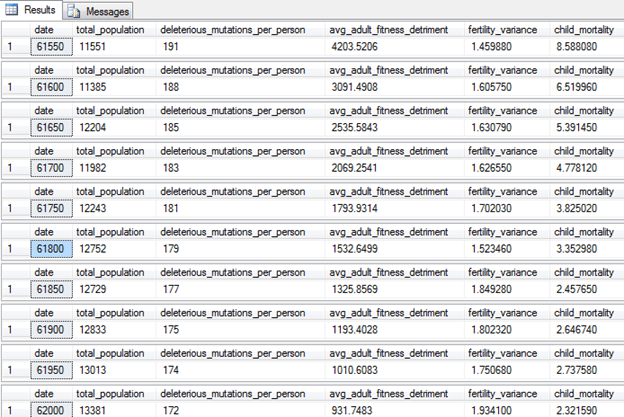

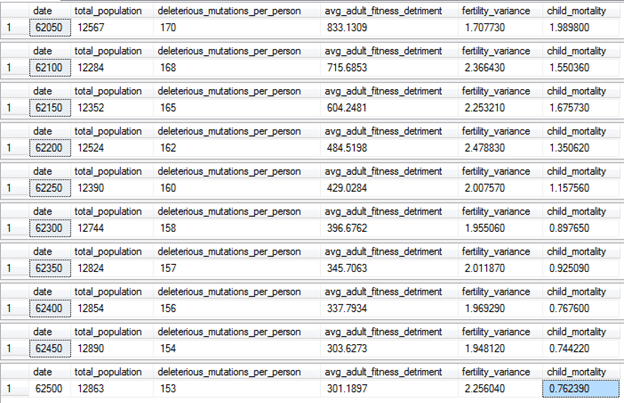

What are the long-term effects of this cycle on our genetic health? Let’s see:

This policy isn’t good—the population has stabilized, but the child mortality has increased further and is now almost 16%, temporarily down from a high of 18.5%. It is possible that 16 to 20% represents a natural equilibrium for the child mortality rate in this version of the model. Or maybe it will push even higher—do we really need to keep trying this long enough to figure that out for sure? This is despite the medical knowledge of the population being the same as it was 1000 years ago when the child mortality rate was 1%. Why are so many children dying? The reason: new genetic diseases. The number of deleterious mutations per person is still slowly increasing. It won’t stop increasing until the child mortality rate is high enough to start purging mutations as fast as they appear. So what is the real solution? We need to add more natural selection back to the system.

Modeling a Family Licensing System

So let’s run the model further. For our next attempt, we’ll limit the population by limiting the total number of families through a family licensing system, while increasing the cultural ideal for the number of children per family up to a healthy ten. To limit the population, the total number of family licenses will be capped at 1000. To further limit the population, the adult failure rate will increase when the population crosses 13,000, representing economic limitations to family growth when the population is too high.

There is also the open question of how one would go about fairly getting a family license. The practical solution: The licenses would be issued once to everyone, then passed down in families through inheritance. In my model, family licenses are preferentially inherited by selected children of the previous license owners. Children from the same family compete with each other to inherit their family’s license through what is called “inheritance selection.” Who inherits the license would be a family decision.

The settings for this model: [Population Model with Family Licensing Settings.sql] (found in source code)

Here are the results:

As you can see, the child mortality rate—and the number of deleterious mutations—are now dropping. Why? Because the high family size in this version of the model allows for natural selection to do its thing.

Four types of natural selection are modeled in my program:

- Child Survival Selection—Children with high genetic load may not survive to adulthood. This selection acts on absolute individual fitness.

- Adult Success Selection—People may die or fail in adulthood for various reasons, which could be related to their genetics. This selection acts on absolute individual fitness.

- Sexual Selection—People with high genetic load may fail to find mates. This selection acts on relative fitness differences between people.

- Inheritance Selection—People with high genetic load are less likely to inherit the family license. This selection acts on relative fitness differences between people.

The possible genes that are generated—all 20,000 of them—each have different effects on each of the four types of selection, and these effects are correlated in configurable ways.

All these methods are effective in reducing genetic load, and the same bad genes can be removed by very different methods of selection. In the Family Licensing model of civilization, most selection comes from sexual selection, followed by inheritance selection. But none of these methods of selection are effective unless family size is high—you must give nature and our sexual instincts enough options to work with.

Modeling Family Medallion Zoning

Can a solution be found that is less draconian than the above family licensing system? By issuing family licenses and preventing anyone without a license from breeding, we’ve solved both our overpopulation problems and our genetic problems. Yet implementing such an authoritarian system won’t be easy and may not be considered ethical, either. Is it possible to loosen the rules and still maintain genetic health? The answer is yes!

To simulate the “Family Medallion Zoning” program—which I now advocate after studying the results of this model—let’s run the model under new settings where it is possible to have a small family outside of the family licensing system. We’ll also decrease the number of licensed families from 1000 to 500.

The family size preferences for these unlicensed families will range from 1 to 2. We’ll also reduce the @percentage_matching parameter to a low level of 5% every 2 years, so to make it less likely that these families will form in the first place. Let’s see what happens:

The population is stable, and the genetic load and child mortality rates are still on the downtrend from what they were after the bad old days of two-child family laws. After 500 years of Family Medallion Zoning, the child mortality rate is finally back under 1%, about where it was when modern medicine was first invented. Even fertility variance has increased, despite the smaller families being allowed—this is due to the decrease in the average adult fitness detriment, allowing family sizes to be larger due to higher genetic fertility and more economic security. Although ideal family size for the licensed couples is set to ten children, families were having difficulty reaching that number.

Projecting Family Medallion Zoning into the Far Future

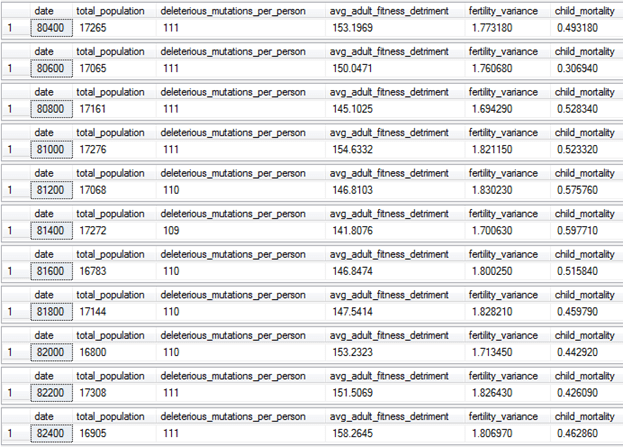

I was curious to what the equilibrium state of mutational load is for Family Medallion Zoning. Using the default version of my model, sexual selection is a bit more efficient for removing genetic load than childhood survival selection. This is due to the random nature of childhood death—deaths happen unpredictably, and who lives and who dies often comes down to luck. In comparison, sexual selection is potentially more objective for determining who is actually the fittest genetically. It is also easier to modulate—humans are an intelligent species, we could make better breeding decisions if we wanted to. Too little selection will result in an accumulation of genetic load. Too much selection will lead to a decrease in genetic diversity or the ascendance of highly attractive individuals who are not actually fit. Yet by having sexual selection as the primary selection method in the future, the potential exists to alter our cultural ideals to modulate between these two extremes. Here’s what the data looks like after running the simulation for another 20,000 years:

After enough time passes, the mutations per person reaches an equilibrium state of 111 per person, and the child mortality rate fluctuates around about half a percent. These values are even lower than what they were in the natural state immediately after the invention of modern medicine. The population has also expanded past the artificial barrier at 13,000—the increased competition between adults that begins once the population hits 13,000 is no longer enough to keep the population around or below this value. Despite this, the population is still stable, since the number of family medallions is capped at 500 and can’t increase, and the other families aren’t breeding at replacement rate.

Uncertainties in the Model

Due to the uncertainty in the nature of human genetics, I don’t know the exact size that the large families need to be to prevent the genetic problems that are discussed in this article. An ideal family size of ten seems completely safe based on the fact that humans are capable of persisting as a species. Relatively smaller family sizes–such as four or five or six children per couple in the “large” families–these may or may not be adequate, depending on uncertain factors such as the deleterious mutation rate in humans and the efficiency of sexual selection in removing genetic load.

And not every family has to be large to prevent genetic load from accumulating, only a certain proportion of them need to be. But what’s the ratio of large families to small families that is ideal? I don’t know the answer to this question, either, and it is not something that my model is going to be able to determine.

Let’s work this problem out logically—first, it depends on whether there is any significant gene flow from the small families to the large families.

If the large families are genetically isolated from the small families and the small families do not breed at replacement rate, then the small families are irrelevant as far as long-term genetics are concerned. The only thing that would matter is the absolute number of lineages among the large families—and whether they alone are enough to preserve our genetic diversity. So how many large families are needed?

My model is not well-equipped to determine the answer to this question either—it is a model of genetic load rather than a model of genetic diversity. Still, we can reason that the higher the total number of family lineages for large families and the more varied their criteria for sexual selection, the more genetic diversity will be preserved.

The other case—when there is gene transfer from the small families to the large families—does have implications on the genetic load. However, limiting the population under this kind of model of civilization would be both difficult to simulate and difficult to manage in the real world. If small-sized families are breeding above replacement level, then how can the population be stabilized? (by that I mean, families that are above replacement level but below the level–whatver it is–needed for there to be enough selection to purge genetic load as fast as it arises) The answer—unless the resources of the natural environment are limited, it would ultimately be stabilized when enough genetic disease accumulates to drive the population down–this is not a good way of stabilizing the population. If the small families are not under any significant selection pressure, we would expect the genetic load to increase by half the mutation rate multiplied by the average number of generations since the small families branched from the large families—this increase would occur every time there is mixing back into the large families. Whether it actually increases by close to this amount would depend on arbitrary factors that are difficult to model in a clear and objective way.

Therefore, I have decided not to attempt to use my model to determine the necessary ratio between large families and small families, since I wouldn’t be able to produce a defensible answer to this open question. I will only say that I believe the total number of large families should be enough—by themselves—to preserve all our human genetic diversity. The absolute number of large families is probably a more important metric for preserving our genetic health than the ratio between large families and small ones.

Furthermore, if certain types of people—such as educated people or people of certain ethnicity—by their culture don’t often have very large families, then any unique genetic diversity they possess will likely be lost after enough generations pass. Therefore, I believe that it is imperative to inform educated people and people of certain ethnicities of this problem in an effort to remove their cultural biases against starting large families.

The numbers in this model—such as the exact number of years and the exact percentages of child mortality—should not be taken literally. This is why my model is configurable—there are many genetics settings included in the model, such that it can model different genetic contingencies.

But even though the exact nature of genetics is uncertain, the basic patterns described in this simulation are consistent across all reasonable settings, and I believe, all possible contingencies of human genetics. I have been working with this model for about a year and a half, slowly developing it and adding features. Every simulation is a little bit different, partially due to random factors, and the simulation described above is just one example of the many population simulations I’ve done under various settings.

For any reasonable settings of the model, the child mortality rate will gradually creep up in an environment of low natural selection. For any reasonable settings, increasing the typical family size to ten or so for a subset of the population will result in a lower equilibrium state of genetic disease. Given what we know about human genetics, it is not possible to come up with reasonable settings for this model where a population with family size restricted at three or less is stable and healthy in the long-term.

Scientific Disagreement

Some scientists believe that relative methods of selection—where success is determined by comparison between individuals rather than based on absolute fitness—are very efficient for removing genetic load, and therefore, the accumulation of genetic load is not of serious concern. For an example, take this article: http://www.genetics.org/content/191/4/1321

Quoting from the article:

“Under the relative fitness model, we show that ϕ depends jointly on U and the selective effects of new deleterious mutations and that a species could tolerate 10’s or even 100’s of new deleterious mutations per genome each generation.”

“The fitness of each individual with k mutations was calculated as (1 − s)k. In each generation we randomly selected pairs of individuals in proportion to their relative fitnesses”

Unfortunately, their model is flawed because the relative fitness model that they use does not account for variance in the deleteriousness of each mutation. My model does account for this, and it shows that a far more important metric of genetic health than total fitness is total number of mutations.

Any model where the fitness is calculated directly from the number of mutations—with no variance for how deleterious each individual mutation is—is going to be unnaturally efficient for removing genetic load due to lack of any confusion between the number of mutations and the total deleteriousness of all mutations. In my model, the deleteriousness of each possible mutation is calculated individually on a variable scale, based on the @lethality_variance and the @lethality_exponent parameters. We can see that the more variance there is in the deleteriousness of each mutation, the less effective relative fitness type-selection is for removing genetic load.

Furthermore, their model’s results–where relative selection methods such as sexual selection are extremely efficient in removing genetic load–can be replicated in my model by setting @lethality_variance, @variant_variance, and @proportion_purely_recessive all to 0 from the start of the simulation, and by setting @heterozygous_divisor to 1 and by setting @lethality_minimum to 2 and @genes_needed_for_lethal to 1500 and @codeleteriousness to 1 and @mutation_rate to 20, as well as lowering the @child_mort_factor and @adult_mort_factor to 200 each. I do not believe that running the model with those settings gives a realistic view of human genetics.

Relative fitness selection is likely more efficient than absolute fitness selection for removing genetic load, however the advantage is not huge, and it does not cause our genetic problems to disappear.

Synergistic Epistasis

It is also an open question how much synergistic epistasis occurs in the human genome—that is to say, how often deleterious mutations interact with each other to produce more deleteriousness in combination than alone. In my model, synergistic epistasis can be configured to be low or high based on the @codeleteriousness setting.

The model shows that if synergistic epistasis is high, then it takes less time for lack of natural selection to result in a substantial increase in human suffering. On the other hand, if synergistic epistasis is low, then natural selection is less effective for removing genetic load, and even higher family sizes among a larger subset of the population will ultimately be needed.

Conclusions

Despite the uncertainties that remain in human genetics, I would argue that there is conclusive evidence to say that two-child family laws or other policies that prevent the formation of large families will cause long-term damage to our genetic health. The argument is strengthened by the lack of any examples of periods in history–or even among higher animals–where typical number of offspring per fertile adult is lower than about five.

It is clear that in the absence of genetic engineering or some other far-fetched and controversial future technology, public policy must allow for the existence high family size among a large subset of the population.

More Details in Source Code

More details for how the model works can be found in the code comments of the source code, which, again, can be downloaded at the top of this page.